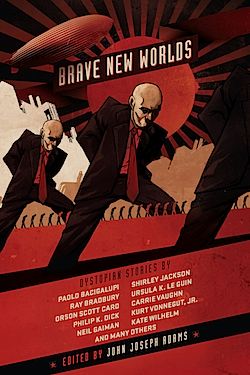

Originally published in the Beth Meacham-edited original anthology Terry’s Universe (Tor, 1988), Kim Stanley Robinson’s dystopian SF tale “The Lunatics” has been reprinted several times, most recently in John Joseph Adams’s superb collection of dystopian SF Brave New Worlds (Night Shade, 2011). Writes Adams in his story intro:

At the end of the nineteenth century, coal mining had become one of the biggest, meanest industries in the United States. Unhealthy working conditions and a reliance on child labor caused accidents and blackened men’s lungs. Crooked business practices like debt bondage and wage-cheating were just part of the misery. But it was dangerous to stand up against the mining companies. Miners didn’t just face losing their jobs—their lives were often at stake, as mining companies fought against unionizing with violence.

The coal miners’ struggles for better conditions were captured in photos and songs that have become a warning for the workers of the world. But in the future, miners might not be so lucky.

What could be worse than working deep beneath the ground, never seeing the light of day? What could be worse than knowing the money in your paycheck was a token worthless outside the company’s store?

[“The Lunatics”] gives us a vision of a mine worse than anything in Pennsylvania. Powered by slavery and jump-started by torment, this mine might as well be hell.

They were very near the center of the moon, Jakob told them. He was the newest member of the bullpen, but already their leader.

“How do you know?” Solly challenged him. It was stifling, the hot air thick with the reek of their sweat, and a pungent stink from the waste bucket in the corner. In the pure black, under the blanket of the rock’s basalt silence, their shifting and snuffling loomed large, defined the size of the pen. “I suppose you see it with your third eye.”

Jakob had a laugh as big as his hands. He was a big man, never a doubt of that. “Of course not, Solly. The third eye is for seeing in the black. It’s a natural sense just like the others. It takes all the data from the rest of the senses, and processes them into a visual image transmitted by the third optic nerve, which runs from the forehead to the sight centers at the back of the brain. But you can only focus it by an act of the will—same as with all the other senses. It’s not magic. We just never needed it till now.”

“So how do you know?”

“It’s a problem in spherical geometry, and I solved it. Oliver and I solved it. This big vein of blue runs right down into the core, I believe, down into the moon’s molten heart where we can never go. But we’ll follow it as far as we can. Note how light we’re getting. There’s less gravity near the center of things.”

“I feel heavier than ever.”

“You are heavy, Solly. Heavy with disbelief.”

“Where’s Freeman?” Hester said in her crow’s rasp.

No one replied.

Oliver stirred uneasily over the rough basalt of the pen’s floor. First Naomi, then mute Elijah, now Freeman. Somewhere out in the shafts and caverns, tunnels and corridors—somewhere in the dark maze of mines, people were disappearing. Their pen was emptying, it seemed. And the other pens?

“Free at last,” Jakob murmured.

“There’s something out there,” Hester said, fear edging her harsh voice, so that it scraped Oliver’s nerves like the screech of an ore car’s wheels over a too-sharp bend in the tracks. “Something out there!”

The rumor had spread through the bullpens already, whispered mouth to ear or in huddled groups of bodies. There were thousands of shafts bored through the rock, hundreds of chambers and caverns. Lots of these were closed off, but many more were left open, and there was room to hide—miles and miles of it. First some of their cows had disappeared. Now it was people too. And Oliver had heard a miner jabbering at the low edge of hysteria, about a giant foreman gone mad after an accident took both his arms at the shoulder—the arms had been replaced by prostheses, and the foreman had escaped into the black, where he preyed on miners off by themselves, ripping them up, feeding on them—

They all heard the steely squeak of a car’s wheel. Up the mother shaft, past cross tunnel Forty; had to be foremen at this time of shift. Would the car turn at the fork to their concourse? Their hypersensitive ears focused on the distant sound; no one breathed. The wheels squeaked, turned their way. Oliver, who was already shivering, began to shake hard.

The car stopped before their pen. The door opened, all in darkness. Not a sound from the quaking miners.

Fierce white light blasted them and they cried out, leaped back against the cage bars vainly. Blinded, Oliver cringed at the clawing of a foreman’s hands, searching under his shirt and pants. Through pupils like pinholes he glimpsed brief black-and-white snapshots of gaunt bodies undergoing similar searches, then blows. Shouts, cries of pain, smack of flesh on flesh, an electric buzzing. Shaving their heads, could it be that time again already? He was struck in the stomach, choked around the neck. Hester’s long wiry brown arms, wrapped around her head. Scalp burned, buzzz all chopped up. Thrown to the rock.

“Where’s the twelfth?” In the foremen’s staccato language. No one answered.

The foremen left, light receding with them until it was black again, the pure dense black that was their own. Except now it was swimming with bright red bars, washing around in painful tears. Oliver’s third eye opened a little, which calmed him, because it was still a new experience; he could make out his companions, dim redblack shapes in the black, huddled over themselves, gasping.

Jakob moved among them, checking for hurts, comforting. He cupped Oliver’s forehead and Oliver said, “It’s seeing already.”

“Good work.” On his knees Jakob clumped to their shit bucket, took off the lid, reached in. He pulled something out. Oliver marveled at how clearly he was able to see all this. Before, floating blobs of color had drifted in the black; but he had always assumed they were afterimages, or hallucinations. Only with Jakob’s instruction had he been able to perceive the patterns they made, the vision that they constituted. It was an act of will. That was the key.

Now, as Jakob cleaned the object with his urine and spit, Oliver found that the eye in his forehead saw even more, in sharp blood etchings. Jakob held the lump overhead, and it seemed it was a little lamp, pouring light over them in a wavelength they had always been able to see, but had never needed before. By its faint ghostly radiance the whole pen was made clear, a structure etched in blood, redblack on black. “Promethium,” Jakob breathed. The miners crowded around him, faces lifted to it. Solly had a little pug nose, and squinched his face terribly in the effort to focus. Hester had a face to go with her voice, stark bones under skin scored with lines. “The most precious element. On Earth our masters rule by it. All their civilization is based on it, on the movement inside it, electrons escaping their shells and crashing into neutrons, giving off heat and more blue as well. So they condemn us to a life of pulling it out of the moon for them.”

He chipped at the chunk with a thumbnail. They all knew precisely its clayey texture, its heaviness, the dull silvery gray of it, which pulsed green under some lasers, blue under others. Jakob gave each of them a sliver of it. “Take it between two molars and crush hard. Then swallow.”

“It’s poison, isn’t it?” said Solly.

“After years and years.” The big laugh, filling the black. “We don’t have years and years, you know that. And in the short run it helps your vision in the black. It strengthens the will.”

Oliver put the soft heavy sliver between his teeth, chomped down, felt the metallic jolt, swallowed. It throbbed in him. He could see the others’ faces, the mesh of the pen walls, the pens farther down the concourse, the robot tracks—all in the lightless black.

“Promethium is the moon’s living substance,” Jakob said quietly. “We walk in the nerves of the moon, tearing them out under the lash of the foremen. The shafts are a map of where the neurons used to be. As they drag the moon’s mind out by its roots, to take it back to Earth and use it for their own enrichment, the lunar consciousness fills us and we become its mind ourselves, to save it from extinction.”

They joined hands: Solly, Hester, Jakob and Oliver. The surge of energy passed through them, leaving a sweet afterglow.

Then they lay down on their rock bed, and Jakob told them tales of his home, of the Pacific dockyards, of the cliffs and wind and waves, and the way the sun’s light lay on it all. Of the jazz in the bars, and how trumpet and clarinet could cross each other. “How do you remember?” Solly asked plaintively. “They turned me blank.”

Jakob laughed hard. “I fell on my mother’s knitting needles when I was a boy, and one went right up my nose. Chopped the hippocampus in two. So all my life my brain has been storing what memories it can somewhere else. They burned a dead part of me, and left the living memory intact.”

“Did it hurt?” Hester croaked.

“The needles? You bet. A flash like the foremen’s prods, right there in the center of me. I suppose the moon feels the same pain, when we mine her. But I’m grateful now, because it opened my third eye right at that moment. Ever since then I’ve seen with it. And down here, without our third eye it’s nothing but the black.”

Oliver nodded, remembering.

“And something out there,” croaked Hester.

Next shift start Oliver was keyed by a foreman, then made his way through the dark to the end of the long, slender vein of blue he was working. Oliver was a tall youth, and some of the shaft was low; no time had been wasted smoothing out the vein’s irregular shape. He had to crawl between the narrow tracks bolted to the rocky uneven floor, scraping through some gaps as if working through a great twisted intestine.

At the shaft head he turned on the robot, a long low-slung metal box on wheels. He activated the laser drill, which faintly lit the exposed surface of the blue, blinding him for some time. When he regained a certain visual equilibrium—mostly by ignoring the weird illumination of the drill beam—he typed instructions into the robot, and went to work drilling into the face, then guiding the robot’s scoop and hoist to the broken pieces of blue. When the big chunks were in the ore cars behind the robot, he jackhammered loose any fragments of the ore that adhered to the basalt walls, and added them to the cars before sending them off.

This vein was tapering down, becoming a mere tendril in the lunar body, and there was less and less room to work in. Soon the robot would be too big for the shaft, and they would have to bore through basalt; they would follow the tendril to its very end, hoping for a bole or a fan.

At first Oliver didn’t much mind the shift’s work. But IR-directed cameras on the robot surveyed him as well as the shaft face, and occasional shocks from its prod reminded him to keep hustling. And in the heat and bad air, as he grew ever more famished, it soon enough became the usual desperate, painful struggle to keep to the required pace.

Time disappeared into that zone of endless agony that was the latter part of a shift. Then he heard the distant klaxon of shift’s end, echoing down the shaft like a cry in a dream. He turned the key in the robot and was plunged into noiseless black, the pure absolute of Nonbeing. Too tired to try opening his third eye, Oliver started back up the shaft by feel, following the last ore car of the shift. It rolled quickly ahead of him and was gone.

In the new silence distant mechanical noises were like creaks in the rock. He measured out the shift’s work, having marked its beginning on the shaft floor: eighty-nine lengths of his body. Average.

It took a long time to get back to the junction with the shaft above his. Here there was a confluence of veins and the room opened out, into an odd chamber some seven feet high, but wider than Oliver could determine in every direction. When he snapped his fingers there was no rebound at all. The usual light at the far end of the low chamber was absent. Feeling sandwiched between two endless rough planes of rock, Oliver experienced a sudden claustrophobia; there was a whole world overhead, he was buried alive…. He crouched and every few steps tapped one rail with his ankle, navigating blindly, a hand held forward to discover any dips in the ceiling.

He was somewhere in the middle of this space when he heard a noise behind him. He froze. Air pushed at his face. It was completely dark, completely silent. The noise squeaked behind him again: a sound like a fingernail, brushed along the banded metal of piano wire. It ran right up his spine, and he felt the hair on his forearms pull away from the dried sweat and stick straight out. He was holding his breath. Very slow footsteps were placed softly behind him, perhaps forty feet away… an airy snuffle, like a big nostril sniffing. For the footsteps to be so spaced out it would have to be….

Oliver loosened his joints, held one arm out and the other forward, tiptoed away from the rail, at right angles to it, for twelve feathery steps. In the lunar gravity he felt he might even float. Then he sank to his knees, breathed through his nose as slowly as he could stand to. His heart knocked at the back of his throat, he was sure it was louder than his breath by far. Over that noise and the roar of blood in his ears he concentrated his hearing to the utmost pitch. Now he could hear the faint sounds of ore cars and perhaps miners and foremen, far down the tunnel that led from the far side of this chamber back to the pens. Even as faint as they were, they obscured further his chances of hearing whatever it was in the cavern with him.

The footsteps had stopped. Then came another metallic scrick over the rail, heard against a light sniff. Oliver cowered, held his arms hard against his sides, knowing he smelled of sweat and fear. Far down the distant shaft a foreman spoke sharply. If he could reach that voice…. He resisted the urge to run for it, feeling sure somehow that whatever was in there with him was fast.

Another scrick. Oliver cringed, trying to reduce his echo profile. There was a chip of rock under his hand. He fingered it, hand shaking. His forehead throbbed and he understood it was his third eye, straining to pierce the black silence and see….

A shape with pillar-thick legs, all in blocks of redblack. It was some sort of….

Scrick. Sniff. It was turning his way. A flick of the wrist, the chip of rock skittered, hitting ceiling and then floor, back in the direction he had come from.

Very slow soft footsteps, as if the legs were somehow… they were coming in his direction.

He straightened and reached above him, hands scrabbling over the rough basalt. He felt a deep groove in the rock, and next to it a vertical hole. He jammed a hand in the hole, made a fist; put the fingers of the other hand along the side of the groove, and pulled himself up. The toes of his boot fit the groove, and he flattened up against the ceiling. In the lunar gravity he could stay there forever. Holding his breath.

Step… step… snuffle, fairly near the floor, which had given him the idea for this move. He couldn’t turn to look. He felt something scrape the hip pocket of his pants and thought he was dead, but fear kept him frozen; and the sounds moved off into the distance of the vast chamber, without a pause.

He dropped to the ground and bolted doubled over for the far tunnel, which loomed before him redblack in the black, exuding air and faint noise. He plunged right in it, feeling one wall nick a knuckle. He took the sharp right he knew was there and threw himself down to the intersection of floor and wall. Footsteps padded by him, apparently running on the rails.

When he couldn’t hold his breath any longer he breathed. Three or four minutes passed and he couldn’t bear to stay still. He hurried to the intersection, turned left and slunk to the bullpen. At the checkpoint the monitor’s horn squawked and a foreman blasted him with a searchlight, pawed him roughly. “Hey!” The foreman held a big chunk of blue, taken from Oliver’s hip pocket. What was this?

“Sorry boss,” Oliver said jerkily, trying to see it properly, remembering the thing brushing him as it passed under. “Must’ve fallen in.” He ignored the foreman’s curse and blow, and fell into the pen tearful with the pain of the light, with relief at being back among the others. Every muscle in him was shaking.

But Hester never came back from that shift.

Sometime later the foremen came back into their bullpen, wielding the lights and the prods to line them up against one mesh wall. Through pinprick pupils Oliver saw just the grossest slabs of shapes, all grainy black-and-gray: Jakob was a big stout man, with a short black beard under the shaved head, and eyes that popped out, glittering even in Oliver’s silhouette world.

“Miners are disappearing from your pen,” the foreman said, in the miners’ language. His voice was like the quartz they tunneled through occasionally: hard, and sparkly with cracks and stresses, as if it might break at any moment into a laugh or a scream.

No one answered.

Finally Jakob said, “We know.”

The foreman stood before him. “They started disappearing when you arrived.”

Jakob shrugged. “Not what I hear.”

The foreman’s searchlight was right on Jakob’s face, which stood out brilliantly, as if two of the searchlights were pointed at each other. Oliver’s third eye suddenly opened and gave the face substance: brown skin, heavy brows, scarred scalp. Not at all the white cutout blazing from the black shadows. “You’d better be careful, miner.”

Loudly enough to be heard from neighboring pens, Jakob said, “Not my fault if something out there is eating us, boss.”

The foreman struck him. Lights bounced and they all dropped to the floor for protection, presenting their backs to the boots. Rain of blows, pain of blows. Still, several pens had to have heard him.

Foremen gone. White blindness returned to black blindness, to the death velvet of their pure darkness. For a long time they lay in their own private worlds, hugging the warm rock of the floor, feeling the bruises blush. Then Jakob crawled around and squatted by each of them, placing his hands on their foreheads. “Oh yeah,” he would say. “You’re okay. Wake up now. Look around you.” And in the after-black they stretched and stretched, quivering like dogs on a scent. The bulks in the black, the shapes they made as they moved and groaned… yes, it came to Oliver again, and he rubbed his face and looked around, eyes shut to help him see. “I ran into it on the way back in,” he said.

They all went still. He told them what had happened. “The blue in your pocket?”

They considered his story in silence. No one understood it.

No one spoke of Hester. Oliver found he couldn’t. She had been his friend. To live without that gaunt crow’s voice….

Sometime later the side door slid up, and they hurried into the barn to eat. The chickens squawked as they took the eggs, the cows mooed as they milked them. The stove plates turned the slightest bit luminous—redblack, again—and by their light his three eyes saw all. Solly cracked and fried eggs. Oliver went to work on his vats of cheese, pulled out a round of it that was ready. Jakob sat at the rear of one cow and laughed as it turned to butt his knee. Splish splish! Splish splish! When he was done he picked up the cow and put it down in front of its hay, where it chomped happily. Animal stink of them all, the many fine smells of food cutting through it. Jakob laughed at his cow, which butted his knee again as if objecting to the ridicule. “Little pig of a cow, little piglet. Mexican cows. They bred for this size, you know. On Earth the ordinary cow is as tall as Oliver, and about as big as this whole pen.”

They laughed at the idea, not believing him. The buzzer cut them off, and the meal was over. Back into their pen, to lay their bodies down.

Still no talk of Hester, and Oliver found his skin crawling again as he recalled his encounter with whatever it was that sniffed through the mines. Jakob came over and asked him about it, sounding puzzled. Then he handed Oliver a rock. “Imagine this is a perfect sphere, like a baseball.”

“Baseball?”

“Like a ball bearing, perfectly round and smooth you know.”

Ah yes. Spherical geometry again. Trigonometry too. Oliver groaned, resisting the work. Then Jakob got him interested despite himself, in the intricacy of it all, the way it all fell together in a complex but comprehensible pattern. Sine and cosine, so clear! And the clearer it got the more he could see: the mesh of the bullpen, the network of shafts and tunnels and caverns piercing the jumbled fabric of the moon’s body… all clear lines of redblack on black, like the metal of the stove plate as it just came visible, and all from Jakob’s clear, patiently fingered, perfectly balanced equations. He could see through rock.

“Good work,” Jakob said when Oliver got tired. They lay there among the others, shifting around to find hollows for their hips.

Silence of the off-shift. Muffled clanks downshaft, floor trembling at a detonation miles of rock away; ears popped as air smashed into the dead end of their tunnel, compressed to something nearly liquid for just an instant. Must have been a Boesman. Ringing silence again.

“So what is it, Jakob?” Solly asked when they could hear each other again.

“It’s an element,” Jakob said sleepily. “A strange kind of element, nothing else like it. Promethium. Number 61 on the periodic table. A rare earth, a lanthanide, an inner transition metal. We’re finding it in veins of an ore called monazite, and in pure grains and nuggets scattered in the ore.”

Impatient, almost pleading: “But what makes it so special?”

For a long time Jakob didn’t answer. They could hear him thinking. Then he said, “Atoms have a nucleus, made of protons and neutrons bound together. Around this nucleus shells of electrons spin, and each shell is either full or trying to get full, to balance with the number of protons—to balance the positive and negative charges. An atom is like a human heart, you see.

“Now promethium is radioactive, which means it’s out of balance, and parts of it are breaking free. But promethium never reaches its balance, because it radiates in a manner that increases its instability rather than the reverse. Promethium atoms release energy in the form of positrons, flying free when neutrons are hit by electrons. But during that impact more neutrons appear in the nucleus. Seems they’re coming from nowhere. So each atom of the blue is a power loop in itself, giving off energy perpetually. Some people say that they’re little white holes, every single atom of them. Burning forever at nine hundred and forty curies per gram. Bringing energy into our universe from somewhere else. Little gateways.”

Solly’s sigh filled the black, expressing incomprehension for all of them. “So it’s poisonous?”

“It’s dangerous, sure, because the positrons breaking away from it fly right through flesh like ours. Mostly they never touch a thing in us, because that’s how close to phantoms we are—mostly blood, which is almost light. That’s why we can see each other so well. But sometimes a beta particle will hit something small on its way through. Could mean nothing or it could kill you on the spot. Eventually it’ll get us all.”

Oliver fell asleep dreaming of threads of light like concentrations of the foremen’s fierce flashes, passing right through him. Shifts passed in their timeless round. They ached when they woke on the warm basalt floor, they ached when they finished the long work shifts. They were hungry and often injured. None of them could say how long they had been there. None of them could say how old they were. Sometimes they lived without light other than the robots’ lasers and the stove plates. Sometimes the foremen visited with their scorching lighthouse beams every off-shift, shouting questions and beating them. Apparently cows were disappearing, cylinders of air and oxygen, supplies of all sorts. None of it mattered to Oliver but the spherical geometry. He knew where he was, he could see it. The three-dimensional map in his head grew more extensive every shift. But everything else was fading away….

“So it’s the most powerful substance in the world,” Solly said. “But why us? Why are we here?”

“You don’t know?” Jakob said.

“They blanked us, remember? All that’s gone.”

But because of Jakob, they knew what was up there: the domed palaces on the lunar surface, the fantastic luxuries of Earth… when he spoke of it, in fact, a lot of Earth came back to them, and they babbled and chattered at the unexpected upwellings. Memories that deep couldn’t be blanked without killing, Jakob said. And so they prevailed after all, in a way.

But there was much that had been burnt forever. And so Jakob sighed. “Yeah yeah, I remember. I just thought—well. We’re here for different reasons. Some were criminals. Some complained.”

“Like Hester!” They laughed.

“Yeah, I suppose that’s what got her here. But a lot of us were just in the wrong place at the wrong time. Wrong politics or skin or whatever. Wrong look on your face.”

“That was me, I bet,” Solly said, and the others laughed at him. “Well I got a funny face, I know I do! I can feel it.”

Jakob was silent for a long time. “What about you?” Oliver asked. More silence. The rumble of a distant detonation, like muted thunder.

“I wish I knew. But I’m like you in that. I don’t remember the actual arrest. They must have hit me on the head. Given me a concussion. I must have said something against the mines, I guess. And the wrong people heard me.”

“Bad luck.”

“Yeah. Bad luck.”

More shifts passed. Oliver rigged a timepiece with two rocks, a length of detonation cord and a set of pulleys, and confirmed over time what he had come to suspect; the work shifts were getting longer. It was more and more difficult to get all the way through one, harder to stay awake for the meals and the geometry lessons during the off-shifts. The foremen came every off-shift now, blasting in with their searchlights and shouts and kicks, leaving in a swirl of afterimages and pain. Solly went out one shift cursing them under his breath, and never came back. Disappeared. The foremen beat them for it and Oliver shouted with rage. “It’s not our fault! There’s something out there, I saw it! It’s killing us!”

Then next shift his little tendril of a vein bloomed, he couldn’t find any rock around the blue: a big bole. He would have to tell the foremen, start working in a crew. He dismantled his clock.

On the way back he heard the footsteps again, shuffling along slowly behind him. This time he was at the entrance to the last tunnel, the pens close behind him. He turned to stare into the darkness with his third eye, willing himself to see the thing. Whoosh of air, a sniff, a footfall on the rail…. Far across the thin wedge of air a beam of light flashed, making a long narrow cone of white talc. Steel tracks gleamed where the wheels of the car burnished them. Pupils shrinking like a snail’s antennae, he stared back at the footsteps, saw nothing. Then, just barely, two points of red: retinas, reflecting the distant lance of light. They blinked. He bolted and ran again, reached the foremen at the checkpoint in seconds. They blinded him as he panted, passed him through and into the bullpen.

After the meal on that shift Oliver lay trembling on the floor of the bullpen and told Jakob about it. “I’m scared, Jakob. Solly, Hester, Freeman, mute Lije, Naomi—they’re all gone. Everyone I know here is gone but us.”

“Free at last,” Jakob said shortly. “Here, let’s do your problems for tonight.”

“I don’t care about them.”

“You have to care about them. Nothing matters unless you do. That blue is the mind of the moon being torn away, and the moon knows it. If we learn what the network says in its shapes, then the moon knows that too, and we’re suffered to live.”

“Not if that thing finds us!”

“You don’t know. Anyway nothing to be done about it. Come on, let’s do the lesson. We need it.”

So they worked on equations in the dark. Both were distracted and the work went slowly; they fell asleep in the middle of it, right there on their faces.

Shifts passed. Oliver pulled a muscle in his back, and excavating the bole he had found was an agony of discomfort. When the bole was cleared it left a space like the interior of an egg, ivory and black and quite smooth, punctuated only by the bluish spots of other tendrils of monazite extending away through the basalt. They left a catwalk across the central space, with decks cut into the rock on each side, and ramps leading to each of the veins of blue; and began drilling on their own again, one man and robot team to each vein. At each shift’s end Oliver rushed to get to the egg-chamber at the same time as all the others, so that he could return the rest of the way to the bullpen in a crowd. This worked well until one shift came to an end with the hoist chock-full of the ore. It took him some time to dump it into the ore car and shut down.

So he had to cross the catwalk alone, and he would be alone all the way back to the pens. Surely it was past time to move the pens closer to the shaft heads! He didn’t want to do this….

Halfway across the catwalk he heard a faint noise ahead of him. Scrick; scriiiiiiik. He jerked to a stop, held the rail hard. Couldn’t reach the ceiling here. Back stabbing its protest, he started to climb over the railing. He could hang from the underside.

He was right on the top of the railing when he was seized up by a number of strong cold hands. He opened his mouth to scream and his mouth was filled with wet clay. The blue. His head was held steady and his ears filled with the same stuff, so that the sounds of his own terrified sharp nasal exhalations were suddenly cut off. Promethium; it would kill him. It hurt his back to struggle on. He was being carried horizontally, ankles whipped, arms tied against his body. Then plugs of the clay were shoved up his nose and in the middle of a final paroxysm of resistance his mind fell away into the black.

The lowest whisper in the world said, “Oliver Pen Twelve.” He heard the voice with his stomach. He was astonished to be alive.

“You will never be given anything again. Do you accept the charge?”

He struggled to nod. I never wanted anything! he tried to say. I only wanted a life like anyone else.

“You will have to fight for every scrap of food, every swallow of water, every breath of air. Do you accept the charge?”

I accept the charge. I welcome it.

“In the eternal night you will steal from the foremen, kill the foremen, oppose their work in every way. Do you accept the charge?” I welcome it.

“You will live free in the mind of the moon. Will you take up this charge?”

He sat up. His mouth was clear, filled only with the sharp electric aftertaste of the blue. He saw the shapes around him: there were five of them, five people there. And suddenly he understood. Joy ballooned in him and he said, “I will. Oh, I will!”

A light appeared. Accustomed as he was either to no light or to intense blasts of it, Oliver at first didn’t comprehend. He thought his third eye was rapidly gaining power. As perhaps it was. But there was also a laser drill from one of the A robots, shot at low power through a cylindrical ceramic electronic element, in a way that made the cylinder glow yellow. Blind like a fish, open-mouthed, weak eyes gaping and watering floods, he saw around him Solly, Hester, Freeman, mute Elijah, Naomi. “Yes,” he said, and tried to embrace them all at once. “Oh, yes.”

They were in one of the long-abandoned caverns, a flat-bottomed bole with only three tendrils extending away from it. The chamber was filled with objects Oliver was more used to identifying by feel or sound or smell: pens of cows and hens, a stack of air cylinders and suits, three ore cars, two B robots, an A robot, a pile of tracks and miscellaneous gear. He walked through it all slowly, Hester at his side. She was gaunt as ever, her skin as dark as the shadows; it sucked up the weak light from the ceramic tube and gave it back only in little points and lines. “Why didn’t you tell me?”

“It was the same for all of us. This is the way.”

“And Naomi?”

“The same for her too; but when she agreed to it, she found herself alone.”

Then it was Jakob, he thought suddenly. “Where’s Jakob?”

Rasped: “He’s coming, we think.”

Oliver nodded, thought about it. “Was it you, then, following me those times? Why didn’t you speak?”

“That wasn’t us,” Hester said when he explained what had happened. She cawed a laugh. “That was something else, still out there….”

Then Jakob stood before them, making them both jump. They shouted and the others all came running, pressed into a mass together. Jakob laughed. “All here now,” he said. “Turn that light off. We don’t need it.”

And they didn’t. Laser shut down, ceramic cooled, they could still see: they could see right into each other, red shapes in the black, radiating joy. Everything in the little chamber was quite distinct, quite visible.

“We are the mind of the moon.”

Without shifts to mark the passage of time Oliver found he could not judge it at all. They worked hard, and they were constantly on the move: always up, through level after level of the mine. “Like shells of the atom, and we’re that particle, busted loose and on its way out.” They ate when they were famished, slept when they had to. Most of the time they worked, either bringing down shafts behind them, or dismantling depots and stealing everything Jakob designated theirs. A few times they ambushed gangs of foremen, killing them with laser cutters and stripping them of valuables; but on Jakob’s orders they avoided contact with foremen when they could. He wanted only material. After a long time—twenty sleeps at least—they had six ore cars of it, all trailing an A robot up long-abandoned and empty shafts, where they had to lay the track ahead of them and pull it out behind, as fast as they could move. Among other items Jakob had an insatiable hunger for explosives; he couldn’t get enough of them.

It got harder to avoid the foremen, who were now heavily armed, and on their guard. Perhaps even searching for them, it was hard to tell. But they searched with their lighthouse beams on full power, to stay out of ambush: it was easy to see them at a distance, draw them off, lose them in dead ends, detonate mines under them. All the while the little band moved up, rising by infinitely long detours toward the front side of the moon. The rock around them cooled. The air circulated more strongly, until it was a constant wind. Through the seismometers they could hear from far below the rumbling of cars, heavy machinery, detonations. “Oh they’re after us all right,” Jakob said. “They’re running scared.”

He was happy with the booty they had accumulated, which included a great number of cylinders of compressed air and pure oxygen. Also vacuum suits for all of them, and a lot more explosives, including ten Boesmans, which were much too big for any ordinary mining. “We’re getting close,” Jakob said as they ate and drank, then tended the cows and hens. As they lay down to sleep by the cars he would talk to them about their work. Each of them had various jobs: mute Elijah was in charge of their supplies, Solly of the robot, Hester of the seismography. Naomi and Freeman were learning demolition, and were in some undefined sense Jakob’s lieutenants. Oliver kept working at his navigation. They had found charts of the tunnel systems in their area, and Oliver was memorizing them, so that he would know at each moment exactly where they were. He found he could do it remarkably well; each time they ventured on he knew where the forks would come, where they would lead. Always upward.

But the pursuit was getting hotter. It seemed there were foremen everywhere, patrolling the shafts in search of them. “Soon they’ll mine some passages and try to drive us into them,” Jakob said. “It’s about time we left.”

“Left?” Oliver repeated.

“Left the system. Struck out on our own.”

“Dig our own tunnel,” Naomi said happily.

“Yes.”

“To where?” Hester croaked.

Then they were rocked by an explosion that almost broke their eardrums, and the air rushed away. The rock around them trembled, creaked, groaned, cracked, and down the tunnel the ceiling collapsed, shoving dust toward them in a roaring whoosh! “A Boesman!” Solly cried.

Jakob laughed out loud. They were all scrambling into their vacuum suits as fast as they could. “Time to leave!” he cried, maneuvering their A robot against the side of the chamber. He put one of their Boesmans against the wall and set the timer. “Okay,” he said over the suit’s intercom. “Now we got to mine like we never mined before. To the surface!”

The first task was to get far enough away from the Boesman that they wouldn’t be killed when it went off. They were now drilling a narrow tunnel and moving the loosened rock behind them to fill up the hole as they passed through it; this loose fill would fly like bullets down a rifle barrel when the Boesman went off. So they made three abrupt turns at acute angles to stop the fill’s movement, and then drilled away from the area as fast as they could. Naomi and Jakob were confident that the explosion of the Boesman would shatter the surrounding rock to such an extent that it would never be possible for anyone to locate the starting point for their tunnel.

“Hopefully they’ll think we did ourselves in,” Naomi said, “either on purpose or by accident.” Oliver enjoyed hearing her light laugh, her clear voice that was so pure and musical compared to Hester’s croaking. He had never known Naomi well before, but now he admired her grace and power, her pulsing energy; she worked harder than Jakob, even. Harder than any of them.

A few shifts into their new life Naomi checked the detonator timer she kept on a cord around her neck. “It should be going off soon. Someone go try and keep the cows and chickens calmed down.” But Solly had just reached the cows’ pen when the Boesman went off. They were all sledgehammered by the blast, which was louder than a mere explosion, something more basic and fundamental: the violent smash of a whole world shutting the door on them. Deafened, bruised, they staggered up and checked each other for serious injuries, then pacified the cows, whose terrified moos they felt in their hands rather than actually heard. The structural integrity of their tunnel seemed okay; they were in an old flow of the mantle’s convection current, now cooled to stasis, and it was plastic enough to take such a blast without shattering. Perfect miners’ rock, protecting them like a mother. They lifted up the cows and set them upright on the bottom of the ore car that had been made into the barn. Freeman hurried back down the tunnel to see how the rear of it looked. When he came back their hearing was returning, and through the ringing that would persist for several shifts he shouted, “It’s walled off good! Fused!”

So they were in a little tunnel of their own. They fell together in a clump, hugging each other and shouting. “Free at last!” Jakob roared, booming out a laugh louder than anything Oliver had ever heard from him. Then they settled down to the task of turning on an air cylinder and recycler, and regulating their gas exchange.

They soon settled into a routine that moved their tunnel forward as quickly and quietly as possible. One of them operated the robot, digging as narrow a shaft as they could possibly work in. This person used only laser drills unless confronted with extremely hard rock, when it was judged worth the risk to set off small explosions, timed by seismometer to follow closely other detonations back in the mines; Jakob and Naomi hoped that the complex interior of the moon would prevent any listeners from noticing that their explosion was anything more than an echo of the mining blast.

Three of them dealt with the rock freed by the robot’s drilling, moving it from the front of the tunnel to its rear, and at intervals pulling up the cars’ tracks and bringing them forward. The placement of the loose rock was a serious matter, because if it displaced much more volume than it had at the front of the tunnel, they would eventually fill in all the open space they had; this was the classic problem of the “creeping worm” tunnel. It was necessary to pack the blocks into the space at the rear with an absolute minimum of gaps, in exactly the way they had been cut, like pieces of a puzzle; they all got very good at the craft of this, losing only a few inches of open space in every mile they dug. This work was the hardest both physically and mentally, and each shift of it left Oliver more tired than he had ever been while mining. Because the truth was all of them were working at full speed, and for the middle team it meant almost running, back and forth, back and forth, back and forth…. Their little bit of open tunnel was only some sixty yards long, but after a while on the midshift it seemed like five hundred.

The three people not working on the rock tended the air and the livestock, ate, helped out with large blocks and the like, and snatched some sleep. They rotated one at a time through the three stations, and worked one shift (timed by detonator timer) at each post. It made for a routine so mesmerizing in its exhaustiveness that Oliver found it very hard to do his calculations of their position in his shift off. “You’ve got to keep at it,” Jakob told him as he ran back from the robot to help the calculating. “It’s not just anywhere we want to come up, but right under the domed city of Selene, next to the rocket rails. To do that we’ll need some good navigation. We get that and we’ll come up right in the middle of the masters who have gotten rich from selling the blue to Earth, and that will be a very gratifying thing I assure you.”

So Oliver would work on it until he slept. Actually it was relatively easy; he knew where they had been in the moon when they struck out on their own, and Jakob had given him the surface coordinates for Selene: so it was just a matter of dead reckoning.

It was even possible to calculate their average speed, and therefore when they could expect to reach the surface. That could be checked against the rate of depletion of their fixed resources—air, water lost in the recycler, and food for the livestock. It took a few shifts of consultation with mute Elijah to determine all the factors reliably, and after that it was a simple matter of arithmetic.

When Oliver and Elijah completed these calculations they called Jakob over and explained what they had done.

“Good work,” Jakob said. “I should have thought of that.”

“But look,” Oliver said, “we’ve got enough air and water, and the robot’s power pack is ten times what we’ll need—same with explosives—it’s only food is a problem. I don’t know if we’ve got enough hay for the cows.”

Jakob nodded as he looked over Oliver’s shoulder and examined their figures. “We’ll have to kill and eat the cows one by one. That’ll feed us and cut down on the amount of hay we need, at the same time.”

“Eat the cows?” Oliver was stunned.

“Sure! They’re meat! People on Earth eat them all the time!”

“Well….” Oliver was doubtful, but under the lash of Hester’s bitter laughter he didn’t say any more.

Still, Jakob and Freeman and Naomi decided it would be best if they stepped up the pace a little bit, to provide them with more of a margin for error. They shifted two people to the shaft face and supplemented the robot’s continuous drilling with hand drill work around the sides of the tunnel, and ate on the run while moving blocks to the back, and slept as little as they could. They were making miles on every shift.

The rock they wormed through began to change in character. The hard, dark, unbroken basalt gave way to lighter rock that was sometimes dangerously fractured. “Anorthosite,” Jakob said. “We’re reaching the crust.” After that every shift brought them through a new zone of rock. Once they tunneled through great layers of calcium feldspar striped with basalt intrusions, so that it looked like badly made brick. Another time they blasted their way through a wall of jasper as hard as steel. Only once did they pass through a vein of the blue; when they did it occurred to Oliver that his whole conception of the moon’s composition had been warped by their mining. He had thought the moon was bursting with promethium, but as they dug across the narrow vein he realized it was uncommon, a loose net of threads in the great lunar body.

As they left the vein behind, Solly picked up a piece of the ore and stared at it curiously, lower eyes shut, face contorted as he struggled to focus his third eye. Suddenly he dashed the chunk to the ground, turned and marched to the head of their tunnel, attacked it with a drill. “I’ve given my whole life to the blue,” he said, voice thick. “And what is it but a Goddamned rock.”

Jakob laughed shortly. They tunneled on, away from the precious metal that now represented to them only a softer material to dig through. “Pick up the pace!” Jakob cried, slapping Solly on the back and leaping over the blocks beside the robot. “This rock has melted and melted again, changing over eons to the stones we see. Metamorphosis,” he chanted, stretching the word out, lingering on the syllable mor until the word became a kind of song. “Metamorphosis. Meta-mor-pho-sis.” Naomi and Hester took up the chant, and mute Elijah tapped his drill against the robot in double time. Jakob chanted over it. “Soon we will come to the city of the masters, the domes of Xanadu with their glass and fruit and steaming pools, and their vases and sports and their fine aged wines. And then there will be a—”

“Metamorphosis.”

And they tunneled ever faster.

Sitting in the sleeping car, chewing on a cheese, Oliver regarded the bulk of Jakob lying beside him. Jakob breathed deeply, very tired, almost asleep. “How do you know about the domes?” Oliver asked him softly. “How do you know all the things that you know?”

“Don’t know,” Jakob muttered. “Everyone knows. Less they burn your brain. Put you in a hole to live out your life. I don’t know much, boy. Make most of it up. Love of a moon. Whatever we need….” And he slept.

They came up through a layer of marble—white marble all laced with quartz, so that it gleamed and sparkled in their lightless sight, and made them feel as though they dug through stone made of their cows’ good milk, mixed with water like diamonds. This went on for a long time, until it filled them up and they became intoxicated with its smooth muscly texture, with the sparks of light lazing out of it. “I remember once we went to see a jazz band,” Jakob said to all of them. Puffing as he ran the white rock along the cars to the rear, stacked it ever so carefully. “It was in Richmond among all the docks and refineries and giant oil tanks and we were so drunk we kept getting lost. But finally we found it—huh!—and it was just this broken-down trumpeter and a back line. He played sitting in a chair and you could just see in his face that his life had been a tough scuffle. His hat covered his whole household. And trumpet is a young man’s instrument, too, it tears your lip to tatters. So we sat down to drink not expecting a thing, and they started up the last song of a set. ‘Bucket’s Got a Hole in It.’ Four bar blues, as simple as a song can get.”

“Metamorphosis,” rasped Hester.

“Yeah! Like that. And this trumpeter started to play it. And they went through it over and over and over. Huh! They must have done it a hundred times. Two hundred times. And sure enough this trumpeter was playing low and half the time in his hat, using all the tricks a broken-down trumpeter uses to save his lip, to hide the fact that it went west thirty years before. But after a while that didn’t matter, because he was playing. He was playing! Everything he had learned in all his life, all the music and all the sorry rest of it, all that was jammed into the poor old ‘Bucket’ and by God it was mind over matter time, because that old song began to roll. And still on the run he broke into it:

“Oh the buck-et’s got a hole in it

Yeah the buck-et’s got a hole in it

Say the buck-et’s got a hole in it.

Can’t buy no beer!”

And over again. Oliver, Solly, Freeman, Hester, Naomi—they couldn’t help laughing. What Jakob came up with out of his unburnt past! Mute Elijah banged a car wall happily, then squeezed the udder of a cow between one verse and the next— “Can’t buy no beer!—Moo!”

They all joined in, breathing or singing it. It fit the pace of their work perfectly: fast but not too fast, regular, repetitive, simple, endless. All the syllables got the same length, a bit syncopated, except “hole,” which was stretched out, and “can’t buy no beer,” which was high and all stretched out, stretched into a great shout of triumph, which was crazy since what it was saying was bad news, or should have been. But the song made it a cry of joy, and every time it rolled around they sang it louder, more stretched out. Jakob scatted up and down and around the tune, and Hester found all kinds of higher harmonics in a voice like a saw cutting steel, and the old tune rocked over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over, in a great passacaglia, in the crucible where all poverty is wrenched to delight: the blues. Metamorphosis. They sang it continuously for two shifts running, until they were all completely hypnotized by it; and then frequently, for long spells, for the rest of their time together.

It was sheer bad luck that they broke into a shaft from below, and that the shaft was filled with armed foremen; and worse luck that Jakob was working the robot, so that he was the first to leap out firing his hand drill like a weapon, and the only one to get struck by return fire before Naomi threw a knotchopper past him and blew the foremen to shreds. They got him on a car and rolled the robot back and pulled up the track and cut off in a new direction, leaving another Boesman behind to destroy evidence of their passing.

So they were all racing around with the blood and stuff still covering them and the cows mooing in distress and Jakob breathing through clenched teeth in double time, and only Hester and Oliver could sit in the car with him and try to tend him, ripping away the pants from a leg that was all cut up. Hester took a hand drill to cauterize the wounds that were bleeding hard, but Jakob shook his head at her, neck muscles bulging out. “Got the big artery inside of the thigh,” he said through his teeth.

Hester hissed. “Come here,” she croaked at Solly and the rest. “Stop that and come here!”

They were in a mass of broken quartz, the fractured clear crystals all pink with oxidation. The robot continued drilling away, the air cylinder hissed, the cows mooed. Jakob’s breathing was harsh and somehow all of them were also breathing in the same way, irregularly, too fast; so that as his breathing slowed and calmed, theirs did too. He was lying back in the sleeping car, on a bed of hay, staring up at the fractured sparkling quartz ceiling of their tunnel, as if he could see far into it. “All these different kinds of rock,” he said, his voice filled with wonder and pain. “You see, the moon itself was the world, once upon a time, and the Earth its moon; but there was an impact, and everything changed.”

They cut a small side passage in the quartz and left Jakob there, so that when they filled in their tunnel as they moved on he was left behind, in his own deep crypt. And from then on the moon for them was only his big tomb, rolling through space till the sun itself died, as he had said it someday would.

Oliver got them back on a course, feeling radically uncertain of his navigational calculations now that Jakob was not there to nod over his shoulder to approve them. Dully he gave Naomi and Freeman the coordinates for Selene. “But what will we do when we get there?” Jakob had never actually made that clear. Find the leaders of the city, demand justice for the miners? Kill them? Get to the rockets of the great magnetic rail accelerators, and hijack one to Earth? Try to slip unnoticed into the populace?

“You leave that to us,” Naomi said. “Just get us there.” And he saw a light in Naomi’s and Freeman’s eyes that hadn’t been there before. It reminded him of the thing that had chased him in the dark, the thing that even Jakob hadn’t been able to explain; it frightened him.

So he set the course and they tunneled on as fast as they ever had. They never sang and they rarely talked; they threw themselves at the rock, hurt themselves in the effort, returned to attack it more fiercely than before. When he could not stave off sleep Oliver lay down on Jakob’s dried blood, and bitterness filled him like a block of the anorthosite they wrestled with.

They were running out of hay. They killed a cow, ate its roasted flesh. The water recycler’s filters were clogging, and their water smelled of urine. Hester listened to the seismometer as often as she could now, and she thought they were being pursued. But she also thought they were approaching Selene’s underside.

Naomi laughed, but it wasn’t like her old laugh. “You got us there, Oliver. Good work.”

Oliver bit back a cry.

“Is it big?” Solly asked.

Hester shook her head. “Doesn’t sound like it. Maybe twice the diameter of the Great Bole, not more.”

“Good,” Freeman said, looking at Naomi.

“But what will we do?” Oliver said.

Hester and Naomi and Freeman and Solly all turned to look at him, eyes blazing like twelve chunks of pure promethium. “We’ve got eight Boesmans left,” Freeman said in a low voice. “All the rest of the explosives add up to a couple more. I’m going to set them just right. It’ll be my best work ever, my masterpiece. And we’ll blow Selene right off into space.”

It took them ten shifts to get all the Boesmans placed to Freeman’s and Naomi’s satisfaction, and then another three to get far enough down and to one side to be protected from the shock of the blast, which luckily for them was directly upward against something that would give, and therefore would have less recoil.

Finally they were set, and they sat in the sleeping car in a circle of six, around the pile of components that sat under the master detonator. For a long time they just sat there cross-legged, breathing slowly and staring at it. Staring at each other, in the dark, in perfect redblack clarity. Then Naomi put both arms out, placed her hands carefully on the detonator’s button. Mute Elijah put his hands on hers—then Freeman, Hester, Solly, finally Oliver—just in the order that Jakob had taken them. Oliver hesitated, feeling the flesh and bone under his hands, the warmth of his companions. He felt they should say something but he didn’t know what it was.

“Seven,” Hester croaked suddenly.

“Six,” Freeman said.

Elijah blew air through his teeth, hard.

“Four,” said Naomi.

“Three!” Solly cried.

“Two,” Oliver said.

And they all waited a beat, swallowing hard, waiting for the moon and the man in the moon to speak to them. Then they pressed down on the button. They smashed at it with their fists, hit it so violently they scarcely felt the shock of the explosion.

They had put on vacuum suits and were breathing pure oxygen as they came up the last tunnel, clearing it of rubble. A great number of other shafts were revealed as they moved into the huge conical cavity left by the Boesmans; tunnels snaked away from the cavity in all directions, so that they had sudden long vistas of blasted tubes extending off into the depths of the moon they had come out of. And at the top of the cavity, struggling over its broken edge, over the rounded wall of a new crater….

It was black. It was not like rock. Spread across it was a spill of white points, some bright, some so faint that they disappeared into the black if you looked straight at them. There were thousands of these white points, scattered over a black dome that was not a dome…. And there in the middle, almost directly overhead: a blue and white ball. Big, bright, blue, distant, rounded; half of it bright as a foreman’s flash, the other half just a shadow…. It was clearly round, a big ball in the… sky. In the sky.

Wordlessly they stood on the great pile of rubble ringing the edge of their hole. Half buried in the broken anorthosite were shards of clear plastic, steel struts, patches of green grass, fragments of metal, an arm, broken branches, a bit of orange ceramic. Heads back to stare at the ball in the sky, at the astonishing fact of the void, they scarcely noticed these things.

A long time passed, and none of them moved except to look around. Past the jumble of dark trash that had mostly been thrown off in a single direction, the surface of the moon was an immense expanse of white hills, as strange and glorious as the stars above. The size of it all! Oliver had never dreamed that everything could be so big.

“The blue must be promethium,” Solly said, pointing up at the Earth. “They’ve covered the whole Earth with the blue we mined.”

Their mouths hung open as they stared at it. “How far away is it?” Freeman asked. No one answered.

“There they all are,” Solly said. He laughed harshly. “I wish I could blow up the Earth too!”

He walked in circles on the rubble of the crater’s rim. The rocket rails, Oliver thought suddenly, must have been in the direction Freeman had sent the debris. Bad luck. The final upward sweep of them poked up out of the dark dirt and glass. Solly pointed at them. His voice was loud in Oliver’s ears, it strained the intercom: “Too bad we can’t fly to the Earth, and blow it up too! I wish we could!”

And mute Elijah took a few steps, leaped off the mound into the sky, took a swipe with one hand at the blue ball. They laughed at him. “Almost got it, didn’t you!” Freeman and Solly tried themselves, and then they all did: taking quick runs, leaping, flying slowly up through space, for five or six or seven seconds, making a grab at the sky overhead, floating back down as if in a dream, to land in a tumble, and try it again…. It felt wonderful to hang up there at the top of the leap, free in the vacuum, free of gravity and everything else, for just that instant.

After a while they sat down on the new crater’s rim, covered with white dust and black dirt. Oliver sat on the very edge of the crater, legs over the edge, so that he could see back down into their sublunar world, at the same time that he looked up into the sky. Three eyes were not enough to judge such immensities. His heart pounded, he felt too intoxicated to move anymore. Tired, drunk. The intercom rasped with the sounds of their breathing, which slowly calmed, fell into a rhythm together. Hester buzzed one phrase of “Bucket” and they laughed softly. They lay back on the rubble, all but Oliver, and stared up into the dizzy reaches of the universe, the velvet black of infinity. Oliver sat with elbows on knees, watched the white hills glowing under the black sky. They were lit by earthlight—earthlight and starlight. The white mountains on the horizon were as sharp-edged as the shards of dome glass sticking out of the rock. And all the time the Earth looked down at him. It was all too fantastic to believe. He drank it in like oxygen, felt it filling him up, expanding in his chest.

“What do you think they’ll do with us when they get here?” Solly asked.

“Kill us,” Hester croaked.

“Or put us back to work,” Naomi added.

Oliver laughed. Whatever happened, it was impossible in that moment to care. For above them a milky spill of stars lay thrown across the infinite black sky, lighting a million better worlds; while just over their heads the Earth glowed like a fine blue lamp; and under their feet rolled the white hills of the happy moon, holed like a great cheese.

The Lunatics © 1988 Kim Stanley Robinson

Kim Stanley Robinson is the bestselling author of fifteen novels, including three series: the Three Californias trilogy (The Wild Shore, 1984; The Gold Coast, 1988; Pacific Edge, 1990), the Mars trilogy (Red Mars, 1992; Green Mars, 1993; Blue Mars, 1996), and the Science in the Capital trilogy (Forty Signs of Rain, 2004; Fifty Degrees Below, 2005; Sixty Days and Counting, 2007). Other novels include Icehenge (1984), The Years of Rice and Salt (2002), and Galileo’s Dream (2009). He is also the author of about seventy short stories, many of which have been collected in The Best of Kim Stanley Robinson (2010). He is the winner of two Hugos, two Nebulas, six Locus Awards, the World Fantasy Award, the British Science Fiction Award, and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award.